The story goes like this.

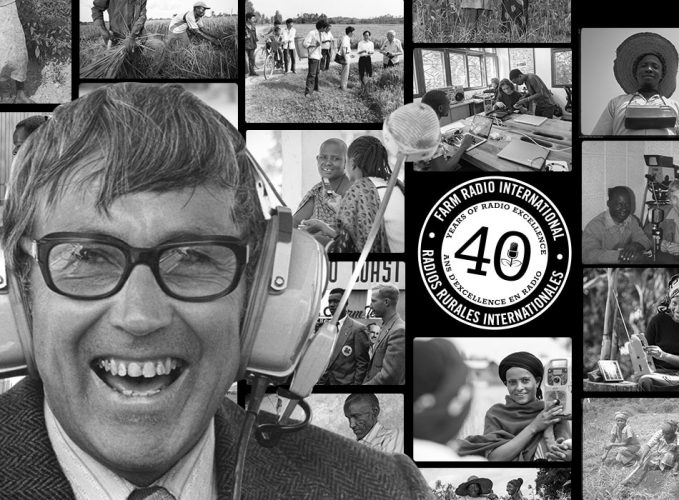

In 1975 George Atkins, then a farm radio broadcaster with CBC, was travelling down a rural road in Zambia.

The group he was with included a number of African broadcasters, there as part of a workshop for farm broadcasters George was working on.

George, ever curious, asked about their latest radio shows.

One of the broadcasters on the bus with him, a man named Abdul from Sierra Leone, said his latest show was on the correct use of spark plugs for tractors.

George was surprised. As he tells it, the conversation went like this:

“How many farmers in Sierra Leone have tractors?” George asked.

“Well, one in 80,000,” Abdul responded.

“And how big an audience do you have?” asked George.

“I’ve got a big audience,” said the broadcaster. “Around 800,000”

George quickly did the mental math.

“You mean you’re talking to 10 farmers out of 800,000 farmers?” he asked.

According to the broadcasters, they didn’t have access to the information relevant to the majority of their listening audience.

“This was where the idea came into my head,” said George.

He proposed writing scripts which featured low cost agricultural tips — things like using manure for fertilizer, or raising oxen for plowing — and sending them to the broadcasters for them to interpret into their local language.

George turned to his colleagues on the bus: “If I were to write that stuff and make it available to you, would you use it?” he asked. They both said “Yes.”

“That’s where the focus of the Farm Radio network came into focus in my mind,” said George.

Four years later, on May 1, 1979, George put together the first package of scripts. From his living room at the family home in Oakville, Ontario, George, with help from his wife Janet, sent the packages to 34 broadcasters in 26 countries around the developing world.

The Developing Countries Farm Radio Network (DCFRN) was born.

Broadcasters around the world would get the scripts, translate them into local languages and transmit the information over the airwaves in local languages to their listeners.

George compiled a team of people, including scientists and agricultural experts from the University of Guelph, his alma mater, and farm broadcasters and journalists around the world to learn about compelling, easy to use farming techniques. The team would design documents explaining the techniques, and send them out to other broadcasters

In one case, scientists at the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology in Kenya confirmed that chickens ate ticks, and proposed using chickens — rather than pesticides — to limit the number of ticks in cattle pens. A decidedly simple idea, but one that might have stayed put had radio across the world not passed the information along.

While tapes and packages were sent to places like Russia, Peru and Sri Lanka, in 2003, we narrowed our focus to sub-Saharan Africa, where we knew we could make the biggest impact. And, in 2008, we made another big change: the Developing Countries Farm Radio Network became Farm Radio International.

Today, we continue the work that George Atkins began so long ago. We still send scripts to broadcasters – along with how to guides, backgrounders and a weekly wire service — though now we do it over the internet.

In 2009, on our 30th anniversary, George recalled the way the organization had grown over the years.

“I just have to pinch myself a little bit now when I think of the people who are helped by this service that is available to them just by turning on their radio.”

Though George passed away late in 2009, we’d like to think that we are still living up to his legacy, now 40 years since its humble start. As George used to say, during the sign off for every broadcast he made:

“Serving agriculture, the basic industry, this is George Atkins.”

Read the latest agricultural information resources and training documents from Farm Radio International, circulated in Farm Radio Resource Pack #111: http://scripts.farmradio.fm/radio-resource-packs/

Listen to the first tape produced by Developing Countries Farm Radio Network.